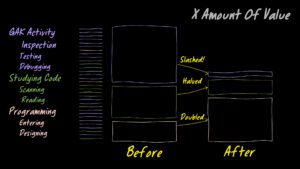

I write things called "microtests" to do my development. Doing this yields me greater success than I’ve had using any other technique in a 40-year career of geekery, so I advocate, wanting to share the technique far & wide.

Before we can talk seriously about how or whether this works, we need a strong grasp of what a microtest is and does, from a strictly technical perspective, w/o all the trappings of the larger method and its attendant polemic.

A single microtest is a small fast chunk of code that we run, outside of our shipping source but depending on it, to confirm or deny simple statements about how that shipping source works, with a particular, but not exclusive, focus on the branching logic within it.

I want to draw your attention to several points embedded in that very long sentence. It’s easy for folks to let these points slide when they first approach the idea. That’s natural, we always bring our existing context with us when we approach a new idea, but if we underplay their significance, it’s easy to head down both theoretical and practical dead-ends.

Externality

First, we have microtest "externality", the property that says the microtest code runs outside the shipping code.

This is a snap from a running app. The app’s called contentment, and when it runs it draws this diagram, interpolated over time, as if I were drawing it by hand.

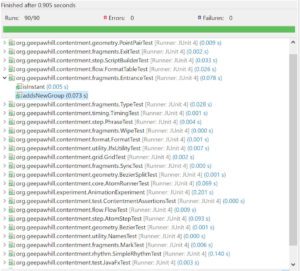

This, on the other hand, is a snap from a microtest run against the contentment app:

Why do they not resemble each other at all? Because the app is the app and the microtests are the microtests. They are two entirely separate programs.

Source-Only Relationship

Second, and this is a little buried, the connection between these two separate apps exists at the source level, not at runtime.

The microtest app does not launch the app and then poke it to see what happens. Rather, both apps rely on some shared code at the source level. The app relies entirely on the shipping source. The microtests rely on the shipping source and the testing source.

This is very important to grasp very early on. In some testing schemes, our tests have a runtime connection to an instance of our app. They literally drive the app and look at the results.

This is not how microtests work. Nearly every modern programming language comes with the ability to use a single source file in two different apps. Microtest schemes make heavy reliance on this capability.

Branchy Focus

Third, microtests focus primarily on branchy logic within the shipping source, with secondary attention to some numerical calculations, and sometimes a small interest in the interface points between the shipping source and the platform on which it runs.

Here’s a file, SyncTest.

{ { package org.geepawhill.contentment.fragments; import static org.assertj.core.api.Assertions.assertThat; import org.geepawhill.contentment.core.Context; import org.geepawhill.contentment.rhythm.SimpleRhythm; import org.junit.*; public class SyncTest { private SimpleRhythm rhythm; private Context context; private Sync sync; @Before public void before() { context = new Context(); rhythm = new SimpleRhythm(); context.setRhythm(rhythm); sync = new Sync(1); } @Test public void continuesIfNotThereYet() { assertThat(sync.interpolate(context, 0)).isTrue(); } @Test public void finishesIfThere() { rhythm.seekHard(2000); assertThat(sync.interpolate(context, 0)).isFalse(); } }

This is a microtest file that uses the shipping source’s Sync class.

The Sync object has just one job, to have its interpolate() method called. If the beat is less than the sync’s target, return true (so that interpolate() will be called again). Otherwise return false (so the caller will stop asking).

The Sync object’s behavior branches logically. There are two branches, and there are two tests, one that selects for each case. (this example is real, if against a rather straightforward responsibility. In the full context, tho, correctly syncing the drawing to the video or audio source is actually the whole point of the contentment app.)

Microtests mostly focus on just this: places where our code changes its behavior, doing one thing in one call and another thing in another call. We also use them for testing calculations. Contentment does a lot of coordinate math. The part of contentment that does geometry has lots of mostly non-branchy code & plenty of microtests to make sure it does its basic algebra & trig the way it’s supposed to.

Sometimes, though not often, microtests will focus on the interface points between the shipping source and its platform. The contentment app uses javafx’s animation framework. There are a couple of classes that serve this functionality to the rest of the app. The microtests here essentially establish that this interface point works correctly.

A more common example out in the wild: a bit of SQL is richer than just ‘select * from table’, and we write some microtests to satisfy ourselves that that bit of SQL gives us the right response in a variety of data cases.

Active Confirmation

The fourth aspect of that long sentence above is caught in the phrase "confirm or deny simple statements". Microtests actively assert about what happens in the shipping source.

Microtests don’t just run a piece of the shipping source and let the programmer notice whether or not the computer caught on fire. Rather, they run that piece with a particular data context and (partially or fully) validate the results of the call.

In the SyncTest file above, the line that says assertThat(sync.interpolate(context, 0)).isFalse(); is calling the interpolate() AND checking that it answers false.

Microtests are active, not passive.

Small and Fast

The fifth and final (for now) aspect of microtests is that they are small and fast.

A typical java microtest is well under 10 lines of code beginning to end. It runs in milliseconds. It tests only a single branch. It doesn’t usually assert everything about the results, but usually only one or two things about them.

The SyncTest above seems trivial, because Sync’s responsibility is, however critical to correct functioning of the app, trivial. but. The average microtest in contentment is five lines long, longest is 20, most of which is taken up by 12 lines of try/catch java noise.

Industrial Logic’s great app for serving online instructional material is a good case. Its 1200 microtests eat under a minute.

These Are Microtests

So there we go. Five important properties of microtests are:

- Externality.

- Source-only relationship to app.

- Branchy focus.

- Active confirmation.

- Small size and high speed.

If we’re talking about microtests, we’re talking about tests that have these properties.

There are many questions waiting in the wings from this starting point. Among others, "Why on earth would I do this?" and "How can I do this when my code doesn’t want me to?"

We can get there. But we can’t get there without remembering these properties.

Pingback: Microtests and Unit Tests for z/OS Applictions – NeoPragma LLC